Dick had treated heroin addicts from Day 1 of his residency in 1966, when there was an epidemic among middle class young white people that drew the attention of the press and the government, and eventually led to a War on Drugs. From the dead overdose victim being dumped on his front porch in 1968 to the prescription drug plague, Dick was familiar with the opiate epidemic.

In the early 2000s, the City and County of San Francisco and the State of California began to adopt a new model for treating patients addicted to opiates, whether prescription medications or heroin. Dick, like most primary care doctors, took it for granted that he would help his patients kick their addiction to cigarettes or alcohol. Now he wanted to add treatment for opiate addiction to primary care.

Dick of course was in the vanguard. He adopted a harm-reduction strategy and became certified to prescribe suboxone, or a combination called Buprenorphine, drugs that had been used in Europe for decades.

As often happened, the US was far behind other countries in adopting public health innovations.

Dick became a leader of the Office-Based Opiate Addiction Treatment program (OBOAT), which trained clinic doctors and private practitioners to manage opiate addiction as part of their primary care practice. No longer would addicts to prescription meds or heroin be required to go to specialized clinics. Their family doctor could provide treatment for their disease of addiction, right along with treating their high blood pressure, diabetes and providing the rest of their primary care.

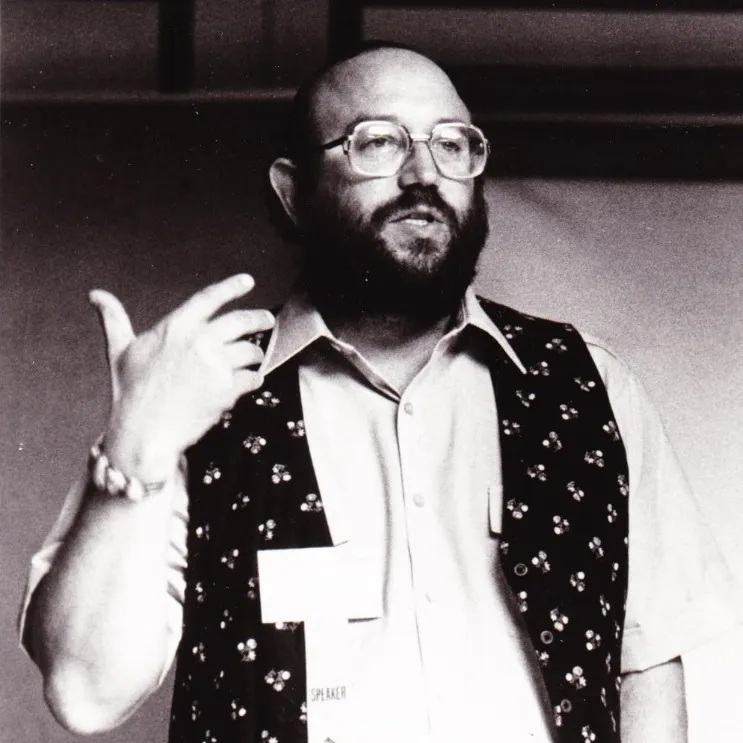

Dick set up meetings to bring together clinicians, researchers, and government officials.

Hard day today,

I have a meeting out at the Jail, after the OBOAT training. Milton Estes, the OBOAT doc at the Jail now, left his private practice in Mill Valley. He’s a good guy.

We may be able to stop the Get Out of Jail and Overdose syndrome. Addicts detox in Jail, due to the relative unavailability of heroin, and then when they’re released they get together with their addict friends, get high and die, because their tolerance has been reduced.

If they’re on buprenorphine, this won’t happen. We’re lucky Michael Hennessey is such a progressive Sheriff; so open to everything that might help people who are still in the early stages of their criminal career.

The OBOAT training had gone well. Dick gave the welcome speech. He reminded everybody to pick up their written materials and leave a urine specimen.

The hotshot from Yale gasped and then hid his eyes. I got one of the only two laughs all day. It was a great meeting but too serious. A hundred people were registered and a hundred and twenty showed up, plus fifteen walk-ins. We ran out of everything. We had to ask the caterer for more food, more chairs.

People are really interested. This is important stuff. We just need to get the doctors in France to write up what they’ve been doing for the past ten years. They claim all these results but they haven’t published anything.